Mothers who give up their child for adoption are called ‘Afstandsmoeders’ (literally ‘distance mothers’) in the Netherlands. In the United Kingdom, they are called birth mothers. Even after giving up your child, you are still a mother. Some women feel like a mother their entire life, despite the ‘distance’. Other mothers feel this less, but to their child, they will always be the biological mother.

Since 1956, it has been possible to put children up for adoption. Birth mothers, who were pregnant at a young age back then, are now 70+ years old. Other birth mothers might already be 80, or even passed away. For a long time, the mothers were invisible. Nothing was known about them, and they remained silent as the grave themselves. At the end of the 80s, a number of birth mothers came out with their stories. Since that moment, a lot of information has been collected (also see: www.wodc.nl/onderzoeksdatabase/2707-onderzoek-afstandmoeders.aspx and www.fiom.nl/kenniscollectie/afstand-ter-adoptie/onderzoeken).

The ‘birth mothers of the past’ are women who put their child up for adoption about thirty (or more) years ago. In those days, shame and taboo played a much bigger role than they do today. Although these birth mothers put their children up for adoption ‘in the past’, they are not in the past. They are the largest group of birth mothers in the Netherlands! Especially around the 70s, children were put up for adoption the most often. Around 1000 women per year put their children up for adoption, forced or not.

A number of these women are now in contact with the children they put up for adoption, or is looking for them. But some of them are still keeping the adoption a secret.

Since the Dutch adoption act of 1956, between 15,000 and 20,000 women in the Netherlands have put their child up for adoption. The exact number is unknown, because this has not been recorded in a clear manner.

In the 70s, there were more than 1000 women a year who put their child up for adoption. Due to better contraceptives, acceptance of single motherhood, more help and better alternatives, the number of women that choose to put their children up for adoption was decreased to 15 to 25 per year.

In the past years, there were about 80 women per year who seek out Fiom with their plans to put their child up for adoption. About 55 to 60 of these women decided against it in the end. They looked after their child themselves or chose for a foster family.

In the 50s and 60s, having had children after you got married was the norm. If pregnancy occurred before marriage, one was literally called a ‘fallen girl’ in the Netherlands, they brought shame to their families. Possibilities to avoid or terminate pregnancy were unavailable: contraceptives were hard to find and abortion was illegal.

Unmarried pregnant women usually went to a shelter for women from the moment their pregnancy became noticeable, for example provided by the Catholic Church. They were able to give birth in secret there, and were taken care of during the period after giving birth. Or they went to stay with family members who lived far away. Usually, they were not really given a choice; there was a lot of pressure to put the baby up for adoption. Many of them were not allowed to see their child. After they got home, nobody talked about it. People used to think it was better to avoid bonding with the child and to forget about everything. Furthermore, it was a taboo to put a child up for adoption, so it had to remain a secret. The birth mothers had to promise never to look for their child.

In the 80s, the number of women that put their child for up adoption decreased. Better contraceptives were available, abortion became legal, and single mothers were no longer seen as shameful. During the same period, people became aware that women who put their child up for adoption were very traumatised by this. With the years, they were more and more open with their stories.

What happens now?

Fiom supports women who want to put their child up for adoption up for adoption after birth. They make sure that reliable information is accessible for those involved, and for professionals. For each decision, a legal procedure is started. Fiom is based on the right one has to be in charge of their own body and life. They believe that adult women should be given the opportunity to make informed decisions about putting their child up for adoption or not. It is important that women are well informed about the effects of adoption and the possibility of other options during the period in which they make their decision. The mother’s thoughts and feelings should be taken into account, so she can make a decision that suits her. If possible and desired, the biological father of the child can be involved with this.

From the experience of Fiom, and from research results it turns out that there is no standard birth mother. The situations in which women put their child up for adoption differ. In general, it can be said that many birth mothers are still young in case of an undesired or unplanned pregnancy. In recent years, they have a different ethnic background more and more often.

In 2011, the report ‘In één klap moeder, en ook weer niet’ (’Suddenly a mother, but also not a mother’) ), based on research, was published. This report offers an insight into the situations and reasons of birth mothers. What makes one decide to put their child up for adoption? More information about this research and the results of it can be found on the Fiom website.

For women who put a child up for adoption in the past, the effects can last their entire lives. They cannot process the past and are very upset about the loss of their child. Thinking back about the time in which they surrendered their child is painful.

Women who are not in contact with the child that they put up for adoption (yet) keep struggling with important questions such as: are they doing well? Were they adopted by nice parents? Was it a good decision in hindsight? Do they blame me?

Because of fear of being judged, these women keep this a secret for years. It makes them feel lonely. Putting a child up for adoption is often a silent and intense sadness. It can lead to depression, low self-esteem, and physical problems.

From research (Bos, P., Reysoo, F. & Werdmuller, A. (2011). ‘In één klap moeder, en ook weer niet’ (‘Suddenly a mother, but also not a mother’) it becomes clear that there could be an accumulation of traumas. The circumstances under which a woman puts her child up for adoption are serious and could be traumatic. Circumstances could for example be rape, prostitution, violence, illegality. The undesired or unplanned pregnancy, which is sometimes only discovered just before birth, is only part of the issue. The separation from the child completes the trauma: complete loss of control, sadness, shame, feelings of guilt, anger, and hiding what happened.

However, not everyone experiences the separation from the child as a trauma. Some women are relieved that their child ended up somewhere nice. They continue their life with little or no efforts. Even years later, when they are approached by their child, they react in a sober and practical manner. They did not experience the separation with their child as painful, or they processed what happened in the past.

The book ‘Eigen bloed– Over moeders die hun kind afstaan ter adoptie’ (’Own blood – About mothers who put their child up for adoption’) includes the stories of eight birth mothers. This book can be obtained through Fiom (https://fiom.nl/kenniscollectie/afstand-ter-adoptie/publicaties/boek-eigen-bloed).

At the same time, there are birth mothers to whom it is still so painful, that they rather not talk about it at all. They do not want contact with their child.

A large group of birth mothers is invisible. They do not look for their child, and their child is not looking for them – it is a widespread misunderstanding that everyone wants to look. How these women are doing is unknown.

The articles above are taken from the Fiom website in May 2017 with permission: www.fiom.nl/kenniscollectie/afstand-ter-adoptie-afstandsmoeders.

Fiom deems it important to raise as much awareness about birth mothers as possible. They want to break the taboo of adoption by providing better information for birth mothers, those involved, professionals, media, and politics.

Besides Fiom, birth mothers can request support from the Dutch foundation De Nederlandse Afstandsmoeder (The Dutch Birth Mother). More information can be found on the website below:

www.denederlandseafstandsmoeder.org

Herkenning, erkenning en bewustwording hebben mij tot een completer mens gemaakt’. zegt fotograaf Ton Sondag, zelf geadopteerd, over zijn zoektocht naar verhalen van anderen uit de adoptiedriehoek. En dat wil hij delen. Hij portretteert kinderen, adoptieouders en geboortemoeders en laat hen openhartig vertellen over de invloed die adoptie heeft op hun leven. Naast deze website, waar steeds nieuwe verhalen op te vinden zullen zijn, is het ook de bedoeling dat er een boek en een expositie tot stand komen met een verzameling van deze verhalen. Om het ware gezicht achter adoptie te laten zien aan een zo groot mogelijk publiek.

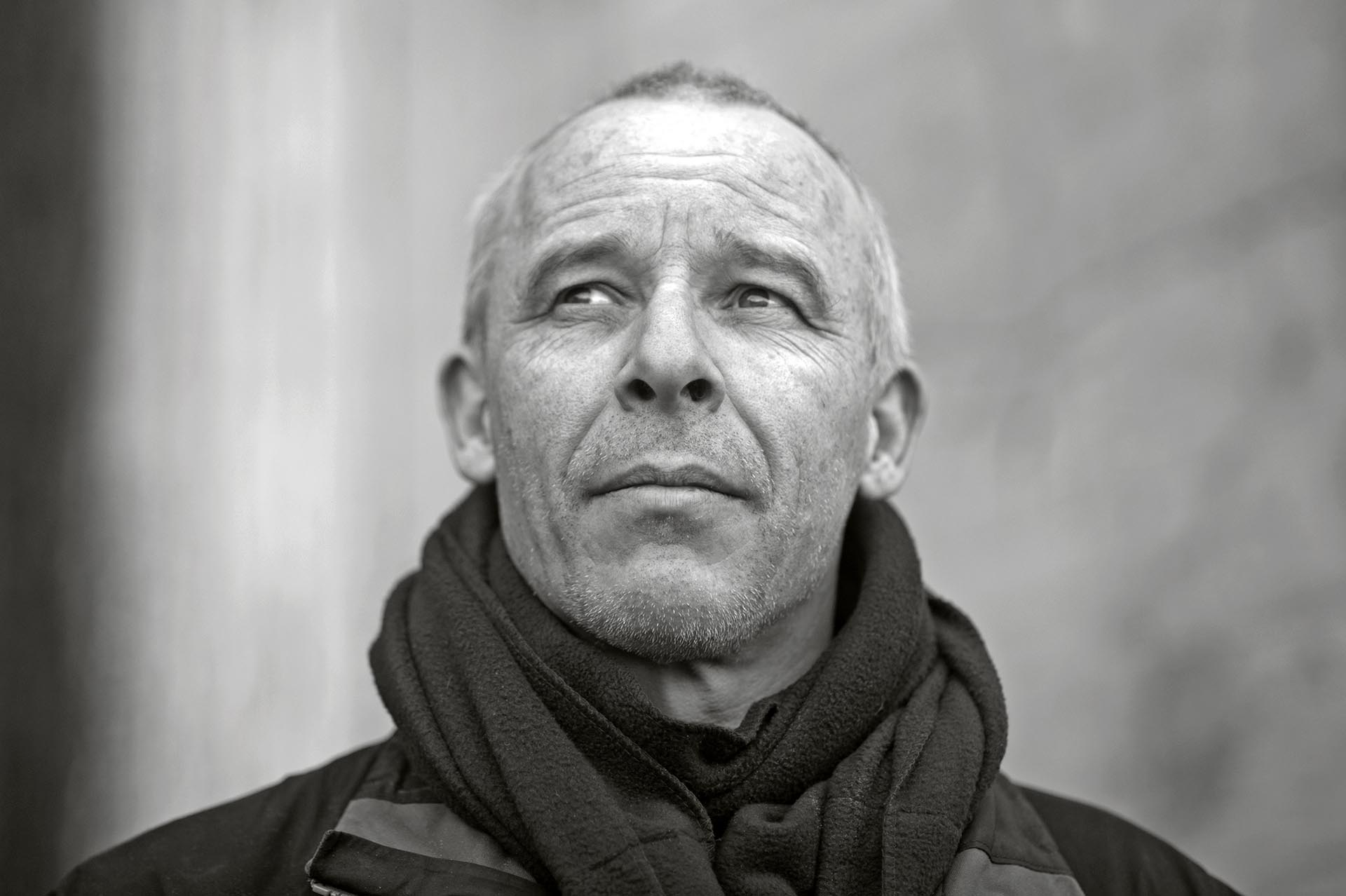

Ton Sondag. (1961)

As a small child, I would often hide inside my head from the big bad world around me, and focus on the details of the surroundings I was in at that moment. This is how I started to examine the world around me more. I think this is how my love for photography was born.

During my childhood my thoughts were racing so much, that photos were more a way of creating souvenirs than visualising my feelings. I was not really aware of that at that moment.

There was also a period in my life that I used my camera as a mask when I was feeling down. I hid myself to be able to keep going.

Travelling and experiences have taught me everything, and being self-taught, this was necessary. First I photographed still images of desolate areas, often with the ocean as a theme, but my work has grown more towards the people person that I am.

The transformation took place 2 years ago, when I received schema therapy. Where there was fear of failure, it was replaced by curiosity.

The birth of Project Adopted.

I am 35 years old and active in my own business. With Storyline media, I make videos and write texts for companies and organisations that are trying to realise a positive impact on society. But most of all, I am an adoptive mother. I wrote the book ‘Hallo lieverd’ (‘Hello, darling’) about my personal experiences regarding the adoption of our daughter Pauline from Nigeria.

Just after the book was published, I read about ‘Project Adopted’ by Ton. It got to me, because I realised once more how complex the topic of adoption actually is. And because I know from personal experience how difficult it can be to share your personal story about it. However, sharing those stories can create something beautiful. Because I believe in the power of stories, I approached Ton and offered my help. This is why I am currently interviewing a number of people who pose for Ton’s photographs, and I write down their stories. Sometimes, this has added value for myself as well; I acquired some new insights. Sometimes, it can be confrontational, sometimes reassuring, but always useful. I am happy to be part of this project.

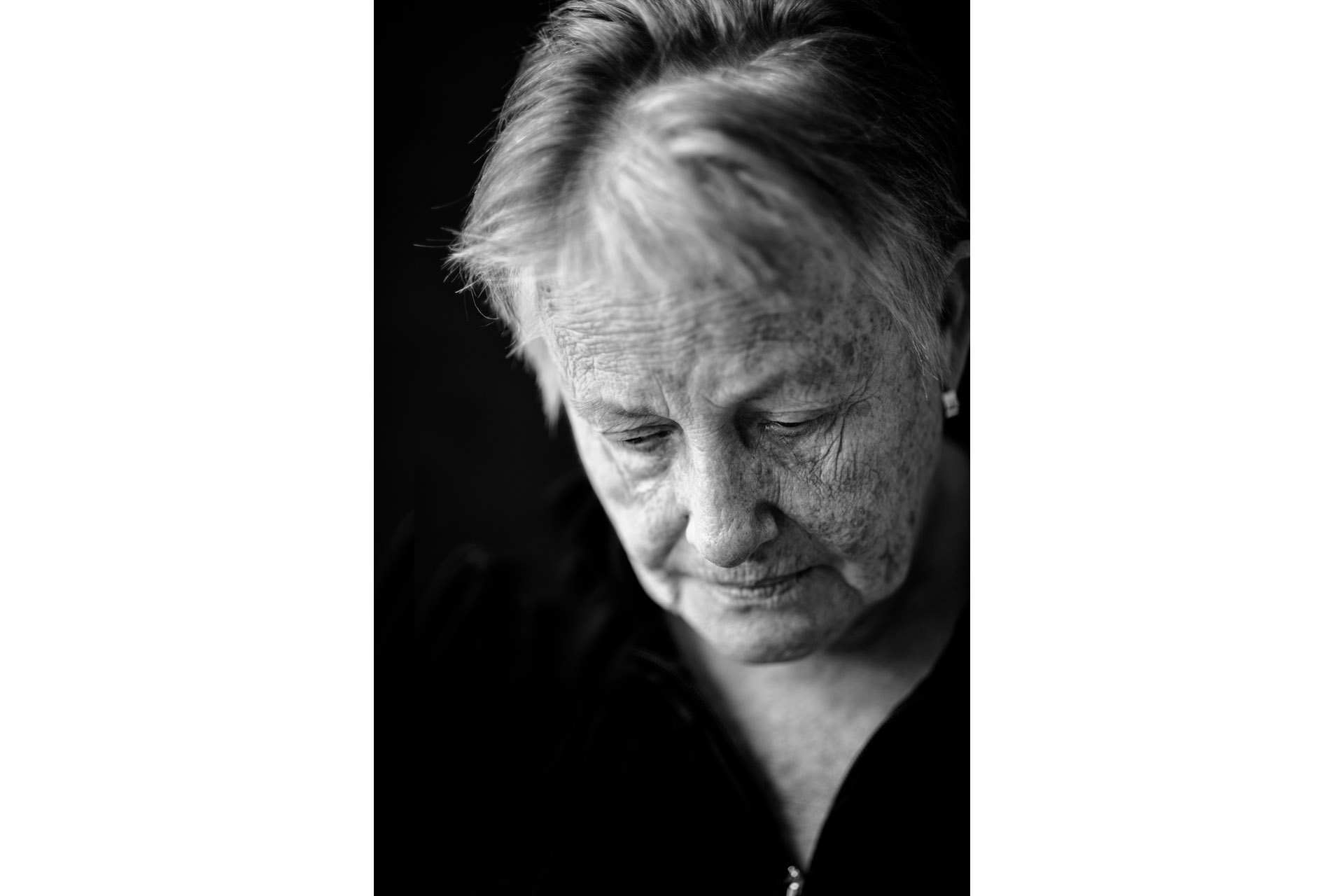

Portrets of children, adoptive parents and birthmothers who candidly talk about the influence that adoption has on their lives.

Safe bonding is not a matter of course. If an unsafe bond occurs so often, how bad is that really?